Computer: You see a hat.

Player: Wear hat.

Computer: You do not have the hat.

Player: Pick up hat.

Computer: I cannot pick the hat up.

Player: Take hat.

Computer: I do not understand take.

Player: Get hat.

Computer: You cannot get the hat because your hands are full of scarves.

Player:

So went more or less every early adventure game, which, whatever exciting puzzle-filled scenario was promised, inevitably turned into a typed conversation with an aggravating, inflexible dunce.

Then one day it occurred to someone that there might be an alternative to having to laboriously describe everything in the game. There were these things, notoriously 1000 times more efficient at painting a picture than words… pictures!

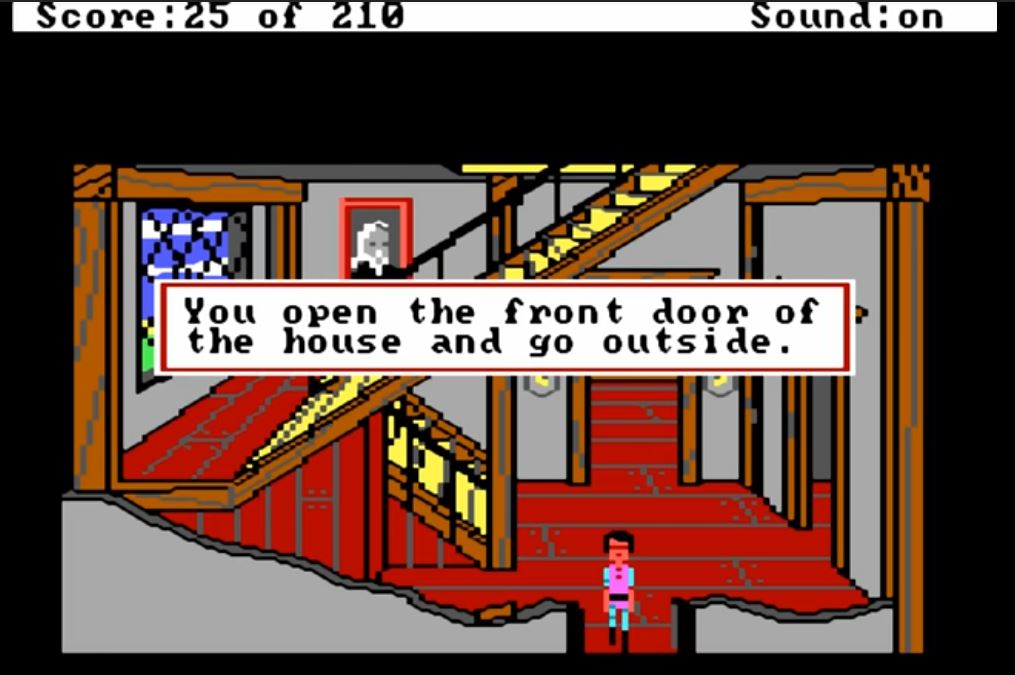

The first adventure game graphics were largely decorative, and you still controlled the game by typing in your best guess at a verb it actually knew, but with the increasing popularity of the electronic computer mouse, it wasn’t long before technology finally reached the stage where if you saw a hat you wanted, you could just click on it. Behold, a genre was born: the aptly named “point-and-click adventure game”!

1984 saw the release of the influential King’s Quest, which let the player move around and interact with a fully realised world consisting of more than just sentences (albeit it was still initially keyboard controlled). It was hugely influential and spawned seven sequels over the next 15 years, documenting the exciting fantasy adventures of Sir Grahame (Graham in later releases), who was sent on a quest from the king, who he would succeed if he, er, succeeded.

If that wasn’t your sort of thing, its developers Sierra On-Line, now Sierra Entertainment, also offered other series including Space Quest (if you liked appalling jokes about science fiction), Police Quest (if you like spending your spare time doing quite boring police work) and Leisure Suit Larry (an at this point inexplicable, vaguely “raunchy” series of games starring a pick-up artist).

But if any one company defined the point-and-click era, it was LucasArts – founded by Star Wars creator George Lucas. Its first adventure game was a fairly primitive effort based on the movie Labyrinth that was notable for two main reasons: a) because Douglas Adams had some input into the design and b) because in the US it made more money than the film.

But it was with a series of comedic games that LucasArts found its niche – starting with Maniac Mansion, a spoof horror game taking off various B-movie tropes. The creators, Ron Gilbert and Gary Winnick, went on to even more success with the Monkey Island games, which gave us pirate fights won by selecting the correct retorts to insults (“You fight like a dairy farmer.” “How appropriate, you fight like a cow.”), and plot points that hinge on whether or not you happen to have a rubber chicken.

Point-and-click did seem ideally suited to comedy, or perhaps it was just that comedy could be used as an excuse for the more deranged elements of the puzzles. One of the more notable examples was Discworld, based on Terry Pratchett’s fantasy comedy novels, which was legendarily difficult – one particularly obtuse puzzle could only be solved by travelling back in time to feed yourself a live frog.

But comedy wasn’t mandatory – 1993’s Myst had players explore an eerily abandoned set of worlds, each containing variously opaque logic puzzles that had to be solved to unravel the plot. Despite being somewhat impenetrable, it was the best-selling PC game of all time until The Sims came along and dislodged it. Revolution’s Broken Sword, a Paris-set conspiracy thriller involving the Knights Templar, managed to prefigure The Da Vinci Code! It also contains a puzzle so infuriating that it received its own Wikipedia page: it turns out that vast and ancient secret societies can be less of a problem than a single angry goat.

By the 2000s the classic point-and-click game was dwindling – most of the adventure game franchises that were still going had attempted to translate themselves into more technologically sophisticated, but generally less charming, 3D versions. But they’ve never entirely disappeared – until their unfortunate (not least for the 250+ employees) and abrupt demise earlier this year, Telltale Games were regularly putting out games that put a 21st century spin on the genre, through updates to old franchises like Monkey Island and digital versions of TV hits like The Walking Dead and Game of Thrones. Various old classics have been remastered with slick graphics and audio to go with the same slightly ropey old puzzles – and 2017 saw the release of Thimbleweed Park, a new game designed to look and feel like an early 90s classic.

But it’s hard to argue that the genre has much appeal beyond nostalgia at this point – even that warm glow is frequently interrupted by a reminder of how often these games ended up being an exasperating exercise in using every object in the vain hope that it might trigger the next bit of plot. For every rewarding puzzle there are three completely illogical bits of guesswork and pixel-hunting, and generally far too much not-actually-as-funny-as-it-thinks-it-is dialogue to sit through.

Thanks for the memories, but it turns out that in 2018, maybe clicking on hats just isn’t enough anymore.

This article was part of the NS’s “Vintage video games week”, click here to read more in the series.